| ATLAS F1 Volume 7, Issue 15 | |||

|

Casablanca Climax | ||

| by Thomas O'Keefe, U.S.A | |||

|

Grands Prix have been held in some pretty exotic locales over the years, but surely the one and only Moroccan Grand Prix, held in the North African coastal city of Casablanca at the Ain-Diab circuit on October 19th 1958, and the circumstances under which it was run, rank right up there as one of Formula One's treasure trove of unique moments. Thomas O'Keefe tells the story of this one of a kind race, and the story of the unforgettable 1958 season

Interestingly, the city of Casablanca was also the setting for the discussion of another great drama, the outcome of which remained in doubt. In January 1943, two months after the film Casablanca appeared, life began to imitate art when the war intrigue that dominated life at "Rick's Place" in the film came to Casablanca in very real terms when Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose the French Morocco city as the location for one of their periodic Councils of War. At the conclusion of this Casablanca conference, it was announced that the Allies had taken off the gloves in opposing the Axis Powers and would now be fighting for the "unconditional surrender" of Germany, Italy and Japan. As in the film Casablanca, Churchill and Roosevelt were doing a bit of improvising here in their roles as the Great Scriptwriters for the Allies, because in those days, early in 1943, the outcome of the war was still far from a sure thing.

To begin with, the Moroccan race was scheduled in a strategic place on the calendar as the last race of the 1958 season, a tempestuous season that was full of firsts and lasts, ups and downs, of triumph and tragedy, and most significantly, a nail-biting nip and tuck quest for the World Championship.

In retrospect, 1958 had more than its fair share of interest and twists and turns for just one season. The World Constructors Championship was introduced for the first time in 1958 and it was as eagerly sought after then, as it is now, by the likes of Ferrari, Vanwall, Cooper, BRM, Lotus and Maserati. Also in 1958, the length of a Grand Prix was reduced from 500 kilometers to 300 kilometers and from 3 hours to 2 hours, and the cars were to run on 130 octane AV gas instead of alcohol-based fuel. The technology of the Grand Prix cars was also changing; indeed, the rear-engined Cooper-Climax jolted the Grand Prix establishment early in the 1958 season by winning the first two races, which forced the famous front-engined soon-to-be dinosaurs like the Ferrari 246, the Maserati 250F and the Vanwall to raise their game to fend off the nimble Coopers. The tire suppliers - Engelbert, Dunlop, Continental and Pirelli - and the war amongst them also turned out to be important factor in the World Championship.

For Graham Hill it was his rookie season, driving a Lotus-Climax, the front-engined Lotus 16. Count Carel Godin de Beaufort continued to campaign his aging Porsche 550RS sporadically. And most singularly, 22 year-old Maria Teresa de Filippis became the first woman to compete in a World Championship Grand Prix, in Spa of all places, in yet another of the plethora of Maserati's 250Fs available in 1958.

Interestingly, although the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix was the only modern World Championship Grand Prix there, French Morocco had hosted Touring Car races back to the 1920's in which Bugattis and Delages made appearances, and a Grand Prix in 1934 was held at the 2-mile ANFA circuit in Casablanca (the predecessor to the 4.724 mile Ain-Diab circuit) that was won by Monagasque Louis Chiron in the famous Alfa Romeo P3 Grand Prix car. Indeed, there were a series of famous North African Grand Prix races during the 1930s, including at Tripoli (now in Libya but then an Italian protectorate) and at Tunis (formerly the Greek city of Carthage), where the Mercedes-Benz and Auto-Union teams displayed their continuing dominance over the competition from Italy, including the 3.1 liter Alpha Romeo P3 as well as the two-engined 6.3 liter Alfa Romeo Bimotore, fielded by then-Alfa Romeo race manager Enzo Ferrari, who would have better luck at the Roulette Wheel of Casablanca in the years to come.

The Casablanca track, located as it was in North Africa, was reasonably accessible to Europe and apparently very popular, as 100,000 people attended the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix. Indeed, the very fact of holding a Grand Prix in Casablanca represented an effort by the sporting authorities of the time - much like today - to expand the geographical reach of Grand Prix racing beyond the provincial boundaries of Europe.

The denouement of the 1958 season at Casablanca was preceded by a seesaw battle between Hawthorn and Moss, Ferrari and Vanwall, with supporting roles played by their respective teammates, Peter Collins for Ferrari and Tony Brooks for Vanwall. Indeed, team orders played a decisive role in the season. It should also be remembered that Ferrari had just come off a particularly debilitating season in 1957 during which the team had not won even one Championship race. Vanwall, meanwhile, was growing ever more muscular as a team, both in its mechanical reliability and speed and in its driver makeup. In short, for different reasons, both of the principal teams were loaded for bear as the 1958 season began.

In a real triumph of racecraft over brute power, the now-famous little No. 14 Cooper with the Rob Walker-trademark white racing stripe around the nose, won the race. Because of the expected heat, Moss's Cooper was bristling with additional air intakes and air deflectors, to help cool the driver, the rear-mounted engine and the front-located radiator, all of which was designed to permit Moss to drive the entire race without a pit stop. Why no pit stops? In part, because the Cooper's bolt-on wheels with five separate wheel studs each would have led to costly, time-consuming pit stops; by contrast, the Ferraris had knock-off wire wheels.

The Argentine surprise was followed by another victory for Ecurie Walker's Cooper at the Monaco Grand Prix, where Monaco specialist Maurice Trintignant (he won the race twice, in 1955 and in 1958, his only Grand Prix wins) survived the retirements of Moss and Hawthorn and won the race, with Ferrari's Musso again finishing second, as he had in Argentina.

But for the rest of the season, power held sway over lightness and the Vanwalls and Ferraris dominated. At Zandvoort for the Dutch Grand Prix, Moss (now back in the Vanwall) won and Hawthorn was the best placed Ferrari, in fifth place, one lap down.

In the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, Hawthorn took pole and finished second as the Vanwalls had mixed results, with Tony Brooks winning the race, teammate Stuart Lewis-Evans finishing third and Stirling Moss finishing dead last - his Vanwall going out on the very first lap after missing a shift, over revving the engine and touching a valve.

At the French Grand Prix, on June 7th 1958, Hawthorn took the third and last of the three Grand Prix wins he had in his career, but the win came at a high price. In the opening two laps of the race, Harry Schell's BRM led briefly, but soon the powerful Ferraris were first, second and third on the fast and dangerous Spa circuit. On lap 9 of the 50 lap race, Luigi Musso, the fiercely competitive and proud Italian driver, challenged his teammate Hawthorn for the lead and crashed, toppling end over end, later dying of his injuries in the hospital. Although the Ferrari of von Trips finished third and Moss was consigned to second place, there was no joy in Maranello that day, because of the loss of the 24 year-old Musso, the last remaining Italian driver of Grand Prix caliber.

Incidentally, this same 1958 French Grand Prix was American Phil Hill's first Grand Prix. Both he and fellow-American and 1952 Indy 500 winner Troy Ruttman were driving the omnipresent Maserati 250F in this race. Within a month, Hill would have joined Ferrari; it would turn out to be one of only two Grands Prix Ruttman qualified and raced in.

On July 19th 1958, the British Grand Prix at Silverstone was won by Peter Collins, finishing 24.2 seconds ahead of his teammate Hawthorn in second place. Moss challenged the Ferraris early on, setting fastest lap, but his engine gave up on him after 25 laps of the 75 lap race. Stuart Lewis-Evans kept Vanwall in the Constructors' Championship hunt with his fourth place finish.

In the very next race, the German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring on August 3rd 1958, the Grim Reaper struck again, as Peter Collins was killed on the 10th lap, going off after Pflanzgarten while in second place and engaged in a battle with ultimate winner Tony Brooks in the Vanwall. Collins's Ferrari had gone wide after the little dip of the Pflanzgarten, his back wheel hit the banking, flipped and threw Collins out of the car and into a tree. He never regained consciousness. Neither Hawthorn nor Moss finished in the points at the Nurburgring, although Moss did lead the race in the opening laps and got fastest lap and Hawthorn was on pole. You can imagine the effect the death of Peter Collins had on his friend and countryman Hawthorn and the overall impact on the Ferrari team of losing both Musso and Collins in less than one month's time.

An interesting sidelight to this race was resolution of a dispute over the legality of Mike Hawthorn's restart on lap 7. The stewards attempted to disqualify Hawthorn for supposedly pushing his car backwards on the racing circuit when he restarted after his spin. Interestingly, it was Stirling Moss who turned out to be the chief witness for Hawthorn's defense since he was running behind Hawthorn and in a position to see what happened. Moss's testimony that he had seen Hawthorn push his car backwards only on the escape road and not on the racing circuit clinched the matter for the stewards: as a result of Moss's sportsmanship, Hawthorn retained second place as well as the extra point for fastest lap.

On September 7th 1958, the Italian Grand Prix was held at Monza, at a time in the season when the battle between Ferrari and Vanwall was tightening. Both teams put on a show of force. Four Ferraris were entered - for Hawthorn, von Trips, Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien. Vanwall entered its three cars and Moss qualified on pole; his Vanwall teammate Tony Brooks was beside him and the Ferrari of Mike Hawthorn wound up in the third spot on the front row.

The effortless style of Tony Brooks proved to be a vital asset that day, as he drove in a way that enabled him to nurse his Dunlop tires, permitting the team to forego one of the pit stops for tires that had been previously planned, in favor of leaving Brooks out there making up time on the Ferraris.

By lap 57 of the 70 lap race, Brooks was making tangible gains on Hawthorn, who was firmly in first place, having led since lap 38. But then Hawthorn's clutch began to slip and Brooks was able to catch and pass Hawthorn in front of the Grandstands on lap 60 and went on to take the win for Vanwall, 20 plus seconds ahead of Hawthorn at the flag. It is clear from the record that Phil Hill was in rare form that day in his Ferrari 246, having set fastest lap and led the race for laps 1 to 4 and laps 35 to 37. At the flag, Phil Hill was in third, only four seconds behind Hawthorn, who was limping home to second with his slipping clutch. Hill had clearly slowed down, pursuant to Ferrari team orders, to allow Hawthorn to score valuable points.

As the teams prepared to send their cars from Europe to North Africa in mid-October 1958, both the Drivers' and Constructors' Championships were on a knife edge and could go either way, depending on the outcome of the Moroccan Grand Prix. Hawthorn had 40 points and Moss had 32 points. Under the system that prevailed at that time, first place was awarded 8 points, second place 6 points and third place 4 points. There was also a point for fastest lap. Because only a driver's best six finishes would count for the Championship, Moss's situation left him with only one option if he wanted to win the World Drivers' Championship: he must win the Casablanca race and set fastest lap and hope Hawthorn did not finish second.

Behind Moss on the track would have been Phil Hill's Ferrari (Phil had qualified fifth and was having another good day) but Ferrari team orders intervened once again and Hill moved over and let his teammate Hawthorn by for second place, which allowed Hawthorn to take sufficient points to win the Drivers' Championship from Moss by exactly one point, 42 to 41. The record books show that the gap from Hawthorn to Hill was 0.8 of a second.

This outcome meant that it was to Hawthorn, not Moss, that the honor would go of being the first Englishman to become a Formula One Drivers' Champion. Moss had won four Grands Prix that year to Hawthorn's one victory, five second places and the occasional fast lap which, taken together with the acquiescence by teammate Phil Hill at Monza and Casablanca, put Hawthorn over the top. As a consolation to Tony Vandervell for the narrow loss of the Drivers' Championship, Vanwall as a constructor took first place, giving Vanwall the honor of winning the first Constructors' Championship over what Vandervell liked to call "those bloody red cars."

Vandervell flew Lewis-Evans home from Casablanca to England on the private plane Vandervell had chartered for the race. Upon arrival in England, Lewis-Evans was treated in the burn unit of East Grimstead hospital but died of his injuries on October 25th 1958. He was the father of two children. According to the local Bexley newspaper, the funeral of Stuart Lewis-Evans, held at Christ Church on Bexleyheath, may well have been the largest the town had ever seen. Among those in attendance from Grand Prix circles were Stirling Moss, Jack Brabham, Jo Bonnier and, of course, Bernie Ecclestone, as well as local dignitaries, businessmen, townsfolk and family members of the fallen driver.

After the Casablanca race, Vandervell never again fielded the Vanwall team in earnest, partly for his own medical reasons and partly because of the loss of Stuart Lewis-Evans. To be sure, the sleek, front-engined Vanwall cars appeared occasionally in 1959 and 1960 and a one-off rear-engined car dubbed the Whale, the VW14, participated in the abortive Intercontinental Formula race for 3 liter cars in 1961, driven by John Surtees. But as a force in Grand Prix racing, the Vanwall Team died with Stuart Lewis-Evans at the end of the 1958 season.

As if the 1958 season had not seen enough tragedy for one year, on January 22th 1959, barely three months after winning the Drivers' Championship, Mike Hawthorn (who had told friends he intended to retire from racing) was killed in his Mark II Jaguar in a road accident near the Guildford bypass in England, apparently trying to catch up to and pass Rob Walker who Hawthorn had spotted up ahead of him in Walker's 300 SL Gullwing Mercedes. As Hawthorn accelerated to overtake Walker, the Jaguar spun out of control when it hit a wet patch of road on the downhill run, slid across to the other side of the dual carriageway and slammed into a tree. When Walker arrived on the scene, Hawthorn was spread out on the back seat of the Jaguar, dead at 29 years old, the last victim of the thrilling but tragic 1958 season that ended in Casablanca.

|

| Thomas O'Keefe | © 2007 autosport.com |

| Send comments to: okeefe@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

Casablanca has always been a place for delicious and mysterious one-off's, often having elements of high drama and put together in an improvisational kind of way. Ingrid Bergman, whose unforgettable performance in the movie Casablanca lit up the screen, reported years after the film was made that for all of the film's popularity and apparent high quality, in fact, the screenwriters were only a few steps ahead of the actors during production. Indeed, because the script itself was a work-in-progress, the end of the film - would Ilsa (played by Bergman) choose Rick (played by Humphrey Bogart) or Lazlo (played by Paul Henreid) - was not known by the actors as the film-in-chief was being shot. Accordingly, Bergman had to act the role of Ilsa in an ambiguous way toward her two suitors to permit the screenwriters to go either way at the end of the film. By the way, sharp-eyed Formula One fans of Casablanca will recall that we had a "Renault" in the film - Capt. Louis Renault, played by Claude Rains, the only character that seemed confident of how it would all turn out.

Casablanca has always been a place for delicious and mysterious one-off's, often having elements of high drama and put together in an improvisational kind of way. Ingrid Bergman, whose unforgettable performance in the movie Casablanca lit up the screen, reported years after the film was made that for all of the film's popularity and apparent high quality, in fact, the screenwriters were only a few steps ahead of the actors during production. Indeed, because the script itself was a work-in-progress, the end of the film - would Ilsa (played by Bergman) choose Rick (played by Humphrey Bogart) or Lazlo (played by Paul Henreid) - was not known by the actors as the film-in-chief was being shot. Accordingly, Bergman had to act the role of Ilsa in an ambiguous way toward her two suitors to permit the screenwriters to go either way at the end of the film. By the way, sharp-eyed Formula One fans of Casablanca will recall that we had a "Renault" in the film - Capt. Louis Renault, played by Claude Rains, the only character that seemed confident of how it would all turn out.

The 1958 Grand Prix of Morocco was a little bit like the film Casablanca and the War Council at Casablanca in several respects: you knew something important was going to happen there and that lots of self-sacrifice would be involved, but you were just not sure how it would all turn out and who Lady Luck would favor when the chips were down.

The 1958 Grand Prix of Morocco was a little bit like the film Casablanca and the War Council at Casablanca in several respects: you knew something important was going to happen there and that lots of self-sacrifice would be involved, but you were just not sure how it would all turn out and who Lady Luck would favor when the chips were down.

The drivers of 1958 were as interesting and varied as their cars. Stirling Moss, driving for Vanwall, was at the apogee of his career, having finished second to Juan Manuel Fangio in the Drivers' Championship for 1955, 1956 and1957. Tony Brooks and Stuart Lewis-Evans rounded out the Vanwall team. Fangio himself, driving the Maserati 250 lightweight, was about to give it all up and, in fact, did retire after the French Grand Prix on July 6th 1958. Mike Hawthorn, Peter Collins, Luigi Musso, Olivier Gendebien and Wolfgang von Trips were the core drivers for Ferrari. Even the peripheral members of the 1958 driver group not involved in the Drivers' Championship were a sparkling lot: Carrol Shelby, Maston Gregory, Jean Behra, Carlos Menditeguy, Horace Gould, Harry Schell, Maurice Trintigant, and Jo Bonnier all drove some Maserati or other during the 1958 season. All these Maseratis were effectively privateers since Maserati had withdrawn as a factory team prior to the 1958 season.

The drivers of 1958 were as interesting and varied as their cars. Stirling Moss, driving for Vanwall, was at the apogee of his career, having finished second to Juan Manuel Fangio in the Drivers' Championship for 1955, 1956 and1957. Tony Brooks and Stuart Lewis-Evans rounded out the Vanwall team. Fangio himself, driving the Maserati 250 lightweight, was about to give it all up and, in fact, did retire after the French Grand Prix on July 6th 1958. Mike Hawthorn, Peter Collins, Luigi Musso, Olivier Gendebien and Wolfgang von Trips were the core drivers for Ferrari. Even the peripheral members of the 1958 driver group not involved in the Drivers' Championship were a sparkling lot: Carrol Shelby, Maston Gregory, Jean Behra, Carlos Menditeguy, Horace Gould, Harry Schell, Maurice Trintigant, and Jo Bonnier all drove some Maserati or other during the 1958 season. All these Maseratis were effectively privateers since Maserati had withdrawn as a factory team prior to the 1958 season.

To top off this unique blend of drivers, 28 year-old Bernie Ecclestone, who had at an earlier point in his career raced both bikes and cars, including a Cooper-Bristol and 500cc F3 Coopers, had purchased two of the Connaught Grand Prix cars from a liquidation sale held in September 1957 by the financially-challenged team. Bernie actually attempted to qualify the Connaught himself as a privateer entrant at Monaco and Silverstone, with Jack Fairman and Ivor Bueb being the usual Connaught drivers. Bernie also managed Vanwall's Stuart Lewis-Evans at this time, a relatively new driver to Formula One who had been successful in the lower formulas. In 1957, Stuart Lewis-Evans had also raced a Connaught, finishing fourth at Monaco in the unique-looking "toothpaste tube" Connaught. Stuart Lewis-Evans and Bernie Ecclestone were both the same age and from the borough of Bexley in London.

To top off this unique blend of drivers, 28 year-old Bernie Ecclestone, who had at an earlier point in his career raced both bikes and cars, including a Cooper-Bristol and 500cc F3 Coopers, had purchased two of the Connaught Grand Prix cars from a liquidation sale held in September 1957 by the financially-challenged team. Bernie actually attempted to qualify the Connaught himself as a privateer entrant at Monaco and Silverstone, with Jack Fairman and Ivor Bueb being the usual Connaught drivers. Bernie also managed Vanwall's Stuart Lewis-Evans at this time, a relatively new driver to Formula One who had been successful in the lower formulas. In 1957, Stuart Lewis-Evans had also raced a Connaught, finishing fourth at Monaco in the unique-looking "toothpaste tube" Connaught. Stuart Lewis-Evans and Bernie Ecclestone were both the same age and from the borough of Bexley in London.

Turning to the modern version of the Casablanca course, the Ain-Diab circuit was itself a unique aspect of the 1958 season, a 4.73 mile circuit located alongside the Atlantic Ocean, which incorporated the Coast Road and the Main Road from Casablanca to Azemmour, into a Grand Prix circuit that was used for a World Championship race only this once, in October 1958. Casablanca had hosted a race a year earlier on October 27, 1957, but it was a non-Championship event, still memorable for Jean Behra's victory in a Maserati 250F factory entry and for the "Asian Flu" virus that sidelined Moss and Collins and weakened Fangio, who nevertheless ran in the race and finished fourth in another works Maserati; Stuart Lewis-Evans finished second to Behra in a Vanwall.

Turning to the modern version of the Casablanca course, the Ain-Diab circuit was itself a unique aspect of the 1958 season, a 4.73 mile circuit located alongside the Atlantic Ocean, which incorporated the Coast Road and the Main Road from Casablanca to Azemmour, into a Grand Prix circuit that was used for a World Championship race only this once, in October 1958. Casablanca had hosted a race a year earlier on October 27, 1957, but it was a non-Championship event, still memorable for Jean Behra's victory in a Maserati 250F factory entry and for the "Asian Flu" virus that sidelined Moss and Collins and weakened Fangio, who nevertheless ran in the race and finished fourth in another works Maserati; Stuart Lewis-Evans finished second to Behra in a Vanwall.

But in one of those twists of fate that make Formula One so fascinating, the established front-engined marques with their powerful 2.5 liter engines were set on their collective ears by the lighter, rear-engined, 1.9 liter Cooper-Climax at the Grand Prix of Argentina, held in Buenos Aires on January 19th 1958. Because of the haste in scheduling the event, which was to be Juan Manuel Fangio's last home Grand Prix, only 10 cars appeared on the grid: six privateer Maserati 250F of mixed provenance and quality, three Ferrari 246 and one dark blue Formula 2-derived Cooper-Climax entered by privateer Rob Walker, to be driven by Vanwall driver Stirling Moss. Vanwall had released Moss to Rob Walker for this race since the Vanwall was not ready that early in the season; nor were the BRMs, which also stayed home. Moss's Cooper qualified seventh, two seconds slower than Fangio, who was on pole in the Maserati.

But in one of those twists of fate that make Formula One so fascinating, the established front-engined marques with their powerful 2.5 liter engines were set on their collective ears by the lighter, rear-engined, 1.9 liter Cooper-Climax at the Grand Prix of Argentina, held in Buenos Aires on January 19th 1958. Because of the haste in scheduling the event, which was to be Juan Manuel Fangio's last home Grand Prix, only 10 cars appeared on the grid: six privateer Maserati 250F of mixed provenance and quality, three Ferrari 246 and one dark blue Formula 2-derived Cooper-Climax entered by privateer Rob Walker, to be driven by Vanwall driver Stirling Moss. Vanwall had released Moss to Rob Walker for this race since the Vanwall was not ready that early in the season; nor were the BRMs, which also stayed home. Moss's Cooper qualified seventh, two seconds slower than Fangio, who was on pole in the Maserati.

During the Argentine race, the Ferraris were the first to pit for new Engelbert tires, allowing Moss to move up in the order. Meanwhile, the Maseratis were reacting badly to the AvGas, a lower grade of fuel than they used in 1957, so the race came down to Moss in the Cooper and Musso and Hawthorn in the Ferraris. Rob Walker's team laid out for a change of tires for Moss's Cooper, which lulled the Ferrari team into laying back on the track. In the end, Moss never came in and won the race, establishing one of the may "Firsts" of the season: the first World Championship race to be won by a rear-engined car since Tazio Nuvolari in an Auto-Union won the Yugoslav Grand Prix in Belgrade in September 1939. In the pits after the race, they checked the Continental tires on the Cooper and it is said that the tires were worn down to the canvas.

During the Argentine race, the Ferraris were the first to pit for new Engelbert tires, allowing Moss to move up in the order. Meanwhile, the Maseratis were reacting badly to the AvGas, a lower grade of fuel than they used in 1957, so the race came down to Moss in the Cooper and Musso and Hawthorn in the Ferraris. Rob Walker's team laid out for a change of tires for Moss's Cooper, which lulled the Ferrari team into laying back on the track. In the end, Moss never came in and won the race, establishing one of the may "Firsts" of the season: the first World Championship race to be won by a rear-engined car since Tazio Nuvolari in an Auto-Union won the Yugoslav Grand Prix in Belgrade in September 1939. In the pits after the race, they checked the Continental tires on the Cooper and it is said that the tires were worn down to the canvas.

This 1958 French Grand Prix was also noteworthy as the last Grand Prix run by Juan Manuel Fangio, who finished fourth in his Maserati 250F (Chassis No. 2532 for the Maserati 250F aficionados), a car later purchased by Ralph Lauren. Fangio did drive again at Monza, on June 29th 1958, in the second year of the so-called Race of Two Worlds between the Indianapolis front-engined roadsters and European sports racers and Grand Prix cars, this time in an Offenhauser-powered Indy roadster, but mechanical failure ruined his race. Fangio had also attempted a run in the Indy 500 earlier in the summer of 1958 in May, but he ultimately pronounced the car he was attempting to qualify unraceworthy and never raced in the Indy 500.

This 1958 French Grand Prix was also noteworthy as the last Grand Prix run by Juan Manuel Fangio, who finished fourth in his Maserati 250F (Chassis No. 2532 for the Maserati 250F aficionados), a car later purchased by Ralph Lauren. Fangio did drive again at Monza, on June 29th 1958, in the second year of the so-called Race of Two Worlds between the Indianapolis front-engined roadsters and European sports racers and Grand Prix cars, this time in an Offenhauser-powered Indy roadster, but mechanical failure ruined his race. Fangio had also attempted a run in the Indy 500 earlier in the summer of 1958 in May, but he ultimately pronounced the car he was attempting to qualify unraceworthy and never raced in the Indy 500.

The likeable Peter Collins had not won a race since 1956 when he had won twice - the Belgian and French Grands Prix. He became a legend for the ultimate act of altruism he performed that year when, in the last race of the 1956 season at Monza, Collins handed over his Lancia-Ferrari to his then-teammate Fangio, who was in a desperate struggle with his perennial adversary Stirling Moss for the World Championship. Although Moss went on to win the race, in one of the offset-drive lowline Maserati 250F built especially for the Monza race, by bringing home the Collins/Fangio Lancia-Ferrari in second place, Fangio gained enough points to take the World Championship away from Moss. To appreciate the depth of this act of kindness, since Collins already had won two races in 1956 and had other good finishes, all he had to do at Monza was to finish in third place, which was where he was when he came into the pits and turned the car over to Fangio. (It should be noted that Luigi Musso - who, unlike Collins, was not in contention for the Championship - had declined to turn over his Lancia-Ferrari to Fangio that day at Monza, although, to be fair about it, Musso had done so once before earlier in the season.)

The likeable Peter Collins had not won a race since 1956 when he had won twice - the Belgian and French Grands Prix. He became a legend for the ultimate act of altruism he performed that year when, in the last race of the 1956 season at Monza, Collins handed over his Lancia-Ferrari to his then-teammate Fangio, who was in a desperate struggle with his perennial adversary Stirling Moss for the World Championship. Although Moss went on to win the race, in one of the offset-drive lowline Maserati 250F built especially for the Monza race, by bringing home the Collins/Fangio Lancia-Ferrari in second place, Fangio gained enough points to take the World Championship away from Moss. To appreciate the depth of this act of kindness, since Collins already had won two races in 1956 and had other good finishes, all he had to do at Monza was to finish in third place, which was where he was when he came into the pits and turned the car over to Fangio. (It should be noted that Luigi Musso - who, unlike Collins, was not in contention for the Championship - had declined to turn over his Lancia-Ferrari to Fangio that day at Monza, although, to be fair about it, Musso had done so once before earlier in the season.)

The inaugural Portuguese Grand Prix was held on August 14th 1958 in Oporto at Lisbon, where Moss was on pole and Hawthorn right beside him on the front row. Hawthorn led for laps 2 to 7, spun off and restarted. In the course of chasing Moss, Hawthorn set fastest lap (and gained a critical World Championship point) and ultimately finished second to Moss and ahead of the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans.

The inaugural Portuguese Grand Prix was held on August 14th 1958 in Oporto at Lisbon, where Moss was on pole and Hawthorn right beside him on the front row. Hawthorn led for laps 2 to 7, spun off and restarted. In the course of chasing Moss, Hawthorn set fastest lap (and gained a critical World Championship point) and ultimately finished second to Moss and ahead of the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans.

Amazingly, relative newcomer Phil Hill went through from the second row of the grid and took the early lead for laps 1 through 4, succeeded by Moss as Hill fell back. Brooks stayed in shouting distance of the leaders back in fourth place, behind Moss, Hill and Hawthorn. Moss led until lap 15, going out with gearbox trouble on lap 17. Brooks also had trouble in the early stages and had to pit on lap 13 to repair an oil leak, leaving him almost a lap down. Hawthorn took over the lead after Moss retired for laps 15 to 34. On lap 30, the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans went out with overheating problems, increasing even more the importance to the Vanwall team of the progress of Tony Brooks through the field.

Amazingly, relative newcomer Phil Hill went through from the second row of the grid and took the early lead for laps 1 through 4, succeeded by Moss as Hill fell back. Brooks stayed in shouting distance of the leaders back in fourth place, behind Moss, Hill and Hawthorn. Moss led until lap 15, going out with gearbox trouble on lap 17. Brooks also had trouble in the early stages and had to pit on lap 13 to repair an oil leak, leaving him almost a lap down. Hawthorn took over the lead after Moss retired for laps 15 to 34. On lap 30, the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans went out with overheating problems, increasing even more the importance to the Vanwall team of the progress of Tony Brooks through the field.

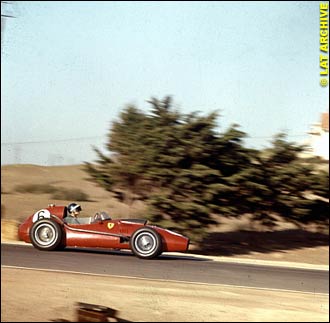

On race day the weather was sunny, mild and dry on the fast and demanding circuit, as befits Casablanca in October, and there were twenty-five cars on the grid. Hawthorn had put his Ferrari on pole and Moss was right next to him on the front row, with the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans in the third slot. Moss did all he had to do that day to win both World Championships. He led the 53-lap race from the outset, he set fastest lap and he won the race by a margin of over 80 seconds on a 4.73-mile circuit where it took 2 minutes and 20 seconds to do a lap.

On race day the weather was sunny, mild and dry on the fast and demanding circuit, as befits Casablanca in October, and there were twenty-five cars on the grid. Hawthorn had put his Ferrari on pole and Moss was right next to him on the front row, with the Vanwall of Stuart Lewis-Evans in the third slot. Moss did all he had to do that day to win both World Championships. He led the 53-lap race from the outset, he set fastest lap and he won the race by a margin of over 80 seconds on a 4.73-mile circuit where it took 2 minutes and 20 seconds to do a lap.

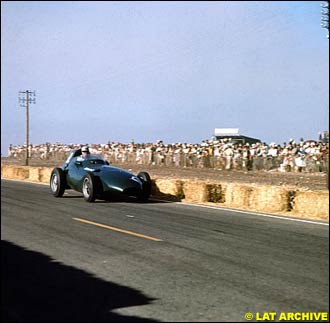

But Tony Vandervell and the rest of the Vanwall team were robbed even of this solace by the death of Stuart Lewis-Evans, 28 years old and a rising star in Formula One, who had crashed on lap 41 of the 53 lap race. Lewis-Evans had spun and hit a tree after his engine seized and his gearbox locked up. The crash had split open the gas tank, which was then ignited by the heat from the exhaust pipes. The Vanwall was front-engined, so the gas tank was mounted behind the driver and the exhaust pipe ran along the left side of the cockpit. Lewis-Evans was able to crawl out of the burning Vanwall, his non-fireproof overalls afire, but then began running in the direction opposite to the corner workers. It is a tragic scene.

But Tony Vandervell and the rest of the Vanwall team were robbed even of this solace by the death of Stuart Lewis-Evans, 28 years old and a rising star in Formula One, who had crashed on lap 41 of the 53 lap race. Lewis-Evans had spun and hit a tree after his engine seized and his gearbox locked up. The crash had split open the gas tank, which was then ignited by the heat from the exhaust pipes. The Vanwall was front-engined, so the gas tank was mounted behind the driver and the exhaust pipe ran along the left side of the cockpit. Lewis-Evans was able to crawl out of the burning Vanwall, his non-fireproof overalls afire, but then began running in the direction opposite to the corner workers. It is a tragic scene.

The Vanwall Team officially announced its withdrawal from racing on January 12th 1959. Many of the Vanwall cars, including the Whale and the Ferrari-based Vanwall called the "ThinWall Special" originally driven by Hawthorn, are preserved today in the Donington Grand Prix Collection run by Tom and Kevin Wheatcroft, located adjacent to the Donington racetrack near Derby, England.

The Vanwall Team officially announced its withdrawal from racing on January 12th 1959. Many of the Vanwall cars, including the Whale and the Ferrari-based Vanwall called the "ThinWall Special" originally driven by Hawthorn, are preserved today in the Donington Grand Prix Collection run by Tom and Kevin Wheatcroft, located adjacent to the Donington racetrack near Derby, England.